A seemingly universal area of disagreement between parents and children is the trade-off between working hard for school and for one’s career versus having fun with friends and other immediate enjoyments. Few parents wish that their kids blew off homework more often in exchange for some instant pleasure. This conflict can be interpreted as a difference in time preference – parents worry more about the long-term consequences of children’s behaviour (such as studying for school) than do the kids themselves. Hence, many parents push their children towards harder work, either through coercion (such as ‘grounding’ children, i.e., not allowing them to spend time with friends) or through sustained indoctrination with a strong work ethic and a striving for success.Now, the assertion that higher inequality implies higher returns to education is a bit vague. In fact, in some Western societies there seems to be a tendency to acquire too much formal education, where a collective move towards more learning on the job could be beneficial. But if we define education as a general set of skills that makes you fit for the working world, then the story makes a lot of sense. Times are getting tougher in developed countries, and so should parenting.

The return to pushing children hard consists of the increased likelihood that they will do well later in life. How important this is to parents depends crucially on the degree of economic inequality, and in particular on the return to education. In an economy where education and effort are highly rewarded and where people with little education struggle, parents will be highly motivated to push their children hard.

Thus, we expect economic inequality to be associated with intensive (authoritarian and authoritative) parenting styles.

In contrast, in an economy where there is little inequality and artists and school dropouts earn only slightly less than doctors and engineers, parents can afford a more relaxed attitude, and permissive parenting should be more prevalent.

Tuesday, 28 October 2014

The rise in inequality and "tiger mom" parenting

The spirit of Gary Becker can be felt in this piece by Matthias Doepke and Fabrizio Zillibotti. It's good fun to read. The central proposition is contained in this passage:

Saturday, 20 September 2014

The joy of creating

Over at "Sketch Me If You Can", former LSE student Lee Zhi Wei has a great story about the joy of creating instead of following the crowd. He draws, other people write papers.

See the whole thing here.

See the whole thing here.

Tuesday, 2 September 2014

Why Germans are not ignorant

As GDP growth in Europe has turned sour again, the opponents of austerity are getting more worried, more vocal and more angry. It's understandable. I agree with them insofar as lack of demand is probably contributing a lot to European stagnation. If there was a way to swiftly implement structural reforms in Europe and at the same time give it a sizeable fiscal stimulus, I would be in for it.

I just have doubts whether some in the anti-austerity camp are able to imagine that the German government could ever think beyond economics. For Simon Wren-Lewis, failure to implement fiscal stimulus can only be the result of either "ignorance or greed". Paul Krugman happily echoes the remarks by diagnosing a "refusal to think clearly".

A moment's pause should be enough to see that Wolfgang Schäuble or Angela Merkel are neither very ignorant nor very greedy personalities. Most politicians and businesspeople, inside and outside of Germany, outperform them on both accounts. And so the diagnosis cannot be right. It does not advance the debate about solving Europe's problems, instead catering to an audience who has already made up its mind about the issue.

Economists in general have a tendency to ignore things outside of economic theory. Instead, upon seeing some behaviour not consistent with their favourite theory, they declare people stupid. It's okay to argue something does not make economic sense. But please make an effort first to see whether it does from another angle. Does the German government believe in the "confidence fairy", in expansionary austerity? My bet is that it is well aware of the thin evidence. Is Schäuble deeply satisfied to see Italians miserable? Give me a break. The game being played is different. It is called "Reformdruck".

"Reformdruck" (pressure to reform) is a concept I don't think exists in macroeconomic theory. It has a moral hazard flavour to it, but it is really not about that. The first premise is that many European countries badly need reforms to their political and economic system. This includes the much discussed flexibility in the labour market, but also raising retirement ages, cutting taxes and red tape for businesses, and enforcing tax collection while reducing the size of the shadow economy. The second premise is that reforms only happen when the situation is dire. Political systems are inertial and reforms happen only in bad times. All reforms carry costs and those tend to be avoided until even the most ardent defender of the status quo gives up his vested interests for the greater good. The conclusion is that for Europe to prosper, some countries will have to suffer economically. Only then can the national governments in Rome, Paris, Madrid and elsewhere implement the changes that lead Europe out of the valley.

This is well illustrated with the story "Mr Keuner and the flood tide" by poet Bertold Brecht:

In essence, Mrs Merkel does not want to send a boat to Italy because she hopes Italy will eventually begin to swim. Note how this is not a moral hazard story. Mr Keuner is not pretending to be helpless, being simply too lazy to swim. He is just being human, not mustering the courage to change his behaviour until it becomes inevitable to do so. In Merkel's view then, I think, Italians are not simply shirking and burning German money. But they will only be able to turn their country around when the economic situation is uncomfortable.

This argument is hard to grasp with macroeconomic theory. In our models, labour-market laws and all the structural issues of the economy are one thing, and deficiency of aggregate demand is another. To a New-Keynesian model, structural deficiencies in an economy are typically exogenous and in any case taken care of by the HP-filter. By contrast, a cyclical demand deficiency can and should be adressed by monetary or, at the zero lower bound, fiscal policy. No surprise then that, for the economist living in such a world, anyone demanding structural reforms without sustaining aggregate demand must be "ignorant".

I just have doubts whether some in the anti-austerity camp are able to imagine that the German government could ever think beyond economics. For Simon Wren-Lewis, failure to implement fiscal stimulus can only be the result of either "ignorance or greed". Paul Krugman happily echoes the remarks by diagnosing a "refusal to think clearly".

A moment's pause should be enough to see that Wolfgang Schäuble or Angela Merkel are neither very ignorant nor very greedy personalities. Most politicians and businesspeople, inside and outside of Germany, outperform them on both accounts. And so the diagnosis cannot be right. It does not advance the debate about solving Europe's problems, instead catering to an audience who has already made up its mind about the issue.

Economists in general have a tendency to ignore things outside of economic theory. Instead, upon seeing some behaviour not consistent with their favourite theory, they declare people stupid. It's okay to argue something does not make economic sense. But please make an effort first to see whether it does from another angle. Does the German government believe in the "confidence fairy", in expansionary austerity? My bet is that it is well aware of the thin evidence. Is Schäuble deeply satisfied to see Italians miserable? Give me a break. The game being played is different. It is called "Reformdruck".

"Reformdruck" (pressure to reform) is a concept I don't think exists in macroeconomic theory. It has a moral hazard flavour to it, but it is really not about that. The first premise is that many European countries badly need reforms to their political and economic system. This includes the much discussed flexibility in the labour market, but also raising retirement ages, cutting taxes and red tape for businesses, and enforcing tax collection while reducing the size of the shadow economy. The second premise is that reforms only happen when the situation is dire. Political systems are inertial and reforms happen only in bad times. All reforms carry costs and those tend to be avoided until even the most ardent defender of the status quo gives up his vested interests for the greater good. The conclusion is that for Europe to prosper, some countries will have to suffer economically. Only then can the national governments in Rome, Paris, Madrid and elsewhere implement the changes that lead Europe out of the valley.

This is well illustrated with the story "Mr Keuner and the flood tide" by poet Bertold Brecht:

Mr Keuner was walking through a valley when he suddenly noticed that his feet were walking through water. Then he realised that his valley was in reality an arm of the sea and that high tide was approaching. He immediately stood still in order to look around for a boat, and he remained standing as long as he hoped to see a boat. But when no boat came in sight, he abandoned this hope and hoped that the water would stop rising. Only when the water reached his chin did he abandon even this hope and begin to swim. He had realised that he himself was a boat.

In essence, Mrs Merkel does not want to send a boat to Italy because she hopes Italy will eventually begin to swim. Note how this is not a moral hazard story. Mr Keuner is not pretending to be helpless, being simply too lazy to swim. He is just being human, not mustering the courage to change his behaviour until it becomes inevitable to do so. In Merkel's view then, I think, Italians are not simply shirking and burning German money. But they will only be able to turn their country around when the economic situation is uncomfortable.

This argument is hard to grasp with macroeconomic theory. In our models, labour-market laws and all the structural issues of the economy are one thing, and deficiency of aggregate demand is another. To a New-Keynesian model, structural deficiencies in an economy are typically exogenous and in any case taken care of by the HP-filter. By contrast, a cyclical demand deficiency can and should be adressed by monetary or, at the zero lower bound, fiscal policy. No surprise then that, for the economist living in such a world, anyone demanding structural reforms without sustaining aggregate demand must be "ignorant".

There is, however, one real danger in the pursuit of the German policy stance. Mr Keuner did not see a boat. But what if he had seen his friend on a boat, only to be turned down by him? Germany is a large boat visible to everyone in the valley of the Eurozone. Imposing "Reformdruck" is already harming the friendship with its neighbours. The long term political cost of this might be greater than what most Germans on their comfortable boat imagine.

Sunday, 24 August 2014

Read your paper: this is your soul

My work is not a cold product. It is not an objective account of the research that it tries to explain. It is a window into my soul. It is the product of my care and nurture, much like a child.

It makes me a bit sad to discover this insight so close to the job market. It would have made me a better job market candidate. Now I feel like a parent who has neglected his child for several years: the damage is not irreversible, but opportunities have been missed. I still hope that I can become a better economist and a better "parent" to my work.

Think about it. Does the economist write with great confidence about the importance of her work, or humbly suggest to point attention to an overlooked area of the field? It reveals the type of role he seeks to fulfil in life. Does he write a paper about the existence of equilibrium, or about what an experiment in Kenya teaches us about incentives? It indicates the type of problems occupying his mind. Does he label his paragraphs "Introduction" and "The model" or "Why this matters" and "What explains return predictability"? It shows how much he cares about sticking to rules and conventions. Finally, how much effort has he put into the paper? It lays bare his life priorities.

The "content" of the paper is of course the research project it describes, and this itself reveals much about the personality of the researcher. But the writing itself reveals just as much. Are you arrogant? are you timid? Do you believe in what you write? Do you feel what you do is important? It will show in the way you write.

It took a small little book for me to realise that I have written papers not to express my ideas in the best possible way, but to conform to a scheme. My writing style was guided mostly by the desire to be accepted in the research community. But that is not a very good principal motivation. It transforms the act of writing into a kind of nuisance that is necessary to be published, but somehow separate from the "actual work". That is misguided. A better motivation is to be truthful to the ideas that drive you. This motivation will also make other people listen.

We sometimes live in the illusion that our work could somehow be separate from our private life. It is not; our personality and, yes, our soul connect the two. Writing it down is part of a larger quest that shapes our lives. It is the quest of becoming truthful to ourselves.

The "content" of the paper is of course the research project it describes, and this itself reveals much about the personality of the researcher. But the writing itself reveals just as much. Are you arrogant? are you timid? Do you believe in what you write? Do you feel what you do is important? It will show in the way you write.

It took a small little book for me to realise that I have written papers not to express my ideas in the best possible way, but to conform to a scheme. My writing style was guided mostly by the desire to be accepted in the research community. But that is not a very good principal motivation. It transforms the act of writing into a kind of nuisance that is necessary to be published, but somehow separate from the "actual work". That is misguided. A better motivation is to be truthful to the ideas that drive you. This motivation will also make other people listen.

We sometimes live in the illusion that our work could somehow be separate from our private life. It is not; our personality and, yes, our soul connect the two. Writing it down is part of a larger quest that shapes our lives. It is the quest of becoming truthful to ourselves.

Wednesday, 9 April 2014

Wednesday, 26 March 2014

Good and old advice to young economists

Almost every econ PhD student knows the following two articles, but one more hyperlink in the vast ocean of the internet cannot harm. These are pieces of advice to young economists that come from two academics that are probably at rather opposite ends of the spectrum, both in terms of political views and in terms of writing style. Classic read.

John Cochrane: "Writing Tips for Ph. D. Students"

Paul Krugman: "How I Work."

John Cochrane: "Writing Tips for Ph. D. Students"

Paul Krugman: "How I Work."

Friday, 21 March 2014

Wouter den Haan on the state of modern macro

This Wednesday, my advisor Wouter den Haan gave a public lecture at the LSE titled "Is Everything You Hear About Macroeconomics True?". It was very stimulating. While I disagreed on some points (on which possibly more later), I was impressed by the earnesty with which he criticised the profession and his own work, and at the same time sharply drew the line to unwarranted criticism often heard from journalists and politicans.

Excerpt:

You can listen to the whole thing here and also download the slides.

Excerpt:

Often we get accused of not being open to alternative approaches. I think that's somewhat true. I think people are always somewhat defensive of things which are new. Especially things that are going to threaten your human capital. If you put a lot of effort into building up this human capital to be able to work with these mathematical [DSGE] models, you're not that happy if the new guy says: "No, let's do it another way." But I also think that these alternative approaches would get a lot more attention if they used the same language as the dominant paradigm (for example things like "efficient markets") and if they also understood better what the challenges are.

In particular, the challenges are not so much to generate a crash - our models can do that, too - or to generate volatile asset prices, or to have models that are better than these protoypes [RBC and New-Keynesian models]. The hard part is, if you discipline yourself by choosing parameters, to then get interesting action. There is a bunch of PhD students here, and they know that the hardest part is not to have an idea. The hardest part is to have an idea that is actually going to be quantitatively important if you discipline yourself in choosing things like preferences, technology and market structure.

You can listen to the whole thing here and also download the slides.

Thursday, 20 March 2014

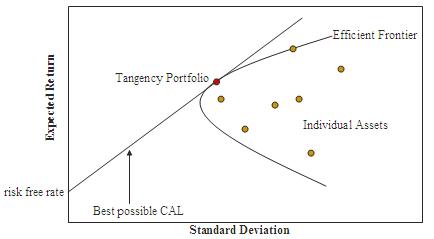

Fallacy of the week: higher risk implies higher return

I remember a conversation at my local bank branch when I wanted to open a small securities account. Their financial advisor asked me what assets I wanted to invest in and offered advice in allocating the portfolio. Most of what she said sounded extremely sensible, but that was mainly because she was a good saleswoman and I hadn't prepared myself well for the meeting.

One part of her advice was that I could choose to invest in equity mutual funds or individual stocks. While the latter would be much more risky, it would also offer the chance of a much higher return.

Over the years, I have heard this argument time and again. In it's general form, it goes somewhat like this:

"Here's an investment opportunity. It's quite risky, but as you know, people who only accept low risk only get low returns. So if you want a high return, invest now!"

The argument sounds somewhat intuitive to me. After all, it's just a description of risk premia, right? Markets reward high risk strategies with high returns. But just as this argument is intuitive, it is also dangerously wrong. Why? Because if you believe it, you will put your hard-earned savings at unnecessary risk by not sufficiently diversifying your portfolio.

This post does not contain any deep thoughts about economics. But I write it because my personal observation suggests that many small individual investors run more or less unconsciously into this simple fallacy.

To illustrate it a little more, suppose you are indeed a small individual investor (if you bother to read this far then you almost certainly are). You can invest money into two stocks, Coca-Cola and Pepsi. You expect both to yield an average return of 4% over the next year. But being stocks, they're both risky: You think that 90% of the time, the return of each stock will fluctuate between 0% and 8%. Now, you could invest all your money in either Coke or Pepsi. Or you can invest half the money in each. If you do the latter, your return will be within 0% and 8% less than 90% of the time, because in order for the return to fall below 0% you need both companies to do badly instead of just one. So this reduces your risk. And what's your expected return? It's the average of 4% and 4%, in other words... still 4%!

You can go ahead and go stockpicking here, and expose yourself to higher risk. Will it earn you higher returns? Sometimes, but on average: not at all. So sober up and stop gambling with your savings.

And what I say does not only apply to stockpicking. It also applies to pouring a lot of money into the purchase of real estate, or putting it all into an equity stake of that tech/green/tax-evading start-up company. Yes, this is very risky because if that one asset implodes your money is gone. But at the same time, you will often also not get a higher return for taking that risk.

Here's a slightly more technical version of the argument. Asset pricing theory tells us that it is not variance which markets compensate with high returns, but covariance with the discount factor: $$ E[R_i]=R_0 (1 - Cov(Q,R_i))$$ where \(R_0\) is the (hypothetical, if you wish) risk-free rate. In the special case of quadratic utility of an investor with a fixed sum to invest over one period, we get the CAPM formula $$ E[R_i]-R_0=\beta_i (E[R^m]-R_0) \text{ with }\beta_i=\frac{Cov(R^m,R_i)}{Var(R^m)}$$ where \( R^m\) is the return on the "market portfolio", the asset allocation of the marginal investor. Now let's rewrite the return on security i as \( R_i = ( R_i - \beta_i R^m) + \beta_i R^m = R_i^d + R_i^{nd}\). Clearly we have $$ E[R^d_i]=R_0 \text{ and } E[R^{nd}_i]=E[R_i]$$ So the market compensates only the risk of the non-diversifiable component \(R^{nd}_i\), but not that of the diversifiable component \(R^d_i\): We have $$\beta_i=\frac{Var[R^{nd}_i]}{Var[R^m]} \neq \frac{Var[R_i]}{Var[R^m]}$$ The fallacy is to put an "=" sign in the last line. Do you think nobody in his right mind would make that mistake? Well, the German Wikipedia does, stating that \(\beta_i \) would be the relative volatility of an asset relative to the market... I would bet that a lot of people read this or similar expositions and then go on picking their favourite stocks instead of just buying the bloody ETF.

Now you might say: "Wait, I still want to buy Google instead of Apple stock because I know that that company is better. I got business sense!" Except this is not about business sense. This is not about knowing which company has a good business model and which doesn't. This is about figuring out which securities are under- or overvalued relative to where they will be in the future. Can you analyse this while working a full-time non-finance job and taking care of the kids on the weekends?

There is one potent argument against diversification of course: costs. Actively managed mutual funds take hefty management fees, so with that strategy you might really need to trade off significantly lower returns in exchange for lower risk. With the rise of ETFs and online brokerage accounts, however, it is nowadays very cheap to buy diversified securities or just build your own diversified portfolio. The case is probably less clear for investing in real estate or non-public companies. Real estate and private equity funds for small individual investors do exist, but here the fees are still pretty high. Still, just because it is costly for you to diversify a risky investment strategy doesn't mean that it is also costly for more sophisticated investors. And if these guys are pricing your strategy, then you will still not earn higher returns by taking higher risk.

Saturday, 8 March 2014

Every time you do optimal policy, Hayek sends you a greeting card

Whether you work as an economist, a management consultant, a computer scientist, an engineer, or indeed in any other profession in which you have to build some sort of mathematical model and solve some kind of optimality problem, you are often running into a very basic tradeoff. If you make a model that captures your object of study very realistically and in detail, you have a hard time figuring out how to optimise it. And if you make a model that you know to optimise, it is often in some important aspects oversimplified. So if you're an economist, you will be hopeless finding optimal policies in large-scale models of the macroeconomy, while nobody will believe the small-scale models you build to think about optimal policy. If you're a management consultant, you can fit some nonlinear model to explain your customer data very well, but good luck communicating a non-linear business strategy to the CEO of your client. If you're a computer scientist, you know the tradeoff as the curse of dimensionality. If you are an engineer, you know that versatility and precision of a machine usually run in opposite directions.

Essentially, we're facing a tradeoff between calibration and optimisation: models that fit the data or process we're looking at very well are hard to optimise well, and models that are easy to optimise usually don't fit the data well.

While this tradeoff exists almost anywhere, and is really just a consequence of the complexity of the world relative to the cognitive capacity of the human mind, I think it is carries a particular meaning in economics.

We know that under the standard assumptions we make (which are satisfied for example by the RBC model), the first welfare theorem holds. That's great, because the question of what the government should do is clear: nothing. The market allocates all resources efficiently. Okay, but that all markets are efficient is such an old joke that you can't even impress your grandmother with it. The world abounds with physical or pecuniary externalities, asymmetric information, bounded rationality or contract enforceability problems, and economics has demonstrated their existence both theoretically and empirically.

In principle, such market failures open the possibility of corrective government intervention. As economists, we often ask: What would an optimal policy intervention look like? As long as policy is not able to restore market efficiency completely (attaining the "first-best", as we say), this becomes quite a difficult problem. The computational complexity of solving a Ramsey problem is much higher than that of calculating a competitive equilibrium.

The reason that is so, at least in macroeconomics, is Hayek's insight that the market is successful because it distributes information decentrally. In the market, every individual need not know all the circumstances of some change which led to resources being allocated differently, as long as they see the prices in the market. I don't need to know that the implementation of some useful technological discovery requires extentive use of tin in order to give up some consumption of it to make room for that discovery; all I need to know is that the price of tin has gone up. By contrast, a central economic planner would need to aggregate all the dispersed information in the economy in order to know how resources should be allocated optimally. Collecting this dispersed information is very problematic, especially when it is about characteristics such as preferences, which are almost impossible to measure.

When we solve a competitive market equilibrium, we take the same position: we only need to solve optimisation problems for agents taking prices as given. Then we can solve for prices using resource constraints in a final step. By contrast, the Ramsey central planner takes into account the impact of policy on prices, and it is this which makes the Ramsey problem difficult. Now, of course solving for prices is also not always easy, especially with heterogenous agents such as in Krusell and Smith. But try to solve a Ramsey problem in the Krusell-Smith model!

And again, while we can calculate optimal policies elegantly in some models, those particular models are often so simplistic that, at least by my impression, people are more often than not very sceptical about the conclusions.

So every time you despair about a Ramsey or other optimal policy problem in economics, and you find yourself faced with a tradeoff of building a simple model nobody believes or not being able to calculate the optimal policy, Hayek is sending you a greeting card from the past: "Remember that the information contained in prices is difficult to centralise".

Essentially, we're facing a tradeoff between calibration and optimisation: models that fit the data or process we're looking at very well are hard to optimise well, and models that are easy to optimise usually don't fit the data well.

While this tradeoff exists almost anywhere, and is really just a consequence of the complexity of the world relative to the cognitive capacity of the human mind, I think it is carries a particular meaning in economics.

We know that under the standard assumptions we make (which are satisfied for example by the RBC model), the first welfare theorem holds. That's great, because the question of what the government should do is clear: nothing. The market allocates all resources efficiently. Okay, but that all markets are efficient is such an old joke that you can't even impress your grandmother with it. The world abounds with physical or pecuniary externalities, asymmetric information, bounded rationality or contract enforceability problems, and economics has demonstrated their existence both theoretically and empirically.

In principle, such market failures open the possibility of corrective government intervention. As economists, we often ask: What would an optimal policy intervention look like? As long as policy is not able to restore market efficiency completely (attaining the "first-best", as we say), this becomes quite a difficult problem. The computational complexity of solving a Ramsey problem is much higher than that of calculating a competitive equilibrium.

The reason that is so, at least in macroeconomics, is Hayek's insight that the market is successful because it distributes information decentrally. In the market, every individual need not know all the circumstances of some change which led to resources being allocated differently, as long as they see the prices in the market. I don't need to know that the implementation of some useful technological discovery requires extentive use of tin in order to give up some consumption of it to make room for that discovery; all I need to know is that the price of tin has gone up. By contrast, a central economic planner would need to aggregate all the dispersed information in the economy in order to know how resources should be allocated optimally. Collecting this dispersed information is very problematic, especially when it is about characteristics such as preferences, which are almost impossible to measure.

When we solve a competitive market equilibrium, we take the same position: we only need to solve optimisation problems for agents taking prices as given. Then we can solve for prices using resource constraints in a final step. By contrast, the Ramsey central planner takes into account the impact of policy on prices, and it is this which makes the Ramsey problem difficult. Now, of course solving for prices is also not always easy, especially with heterogenous agents such as in Krusell and Smith. But try to solve a Ramsey problem in the Krusell-Smith model!

And again, while we can calculate optimal policies elegantly in some models, those particular models are often so simplistic that, at least by my impression, people are more often than not very sceptical about the conclusions.

So every time you despair about a Ramsey or other optimal policy problem in economics, and you find yourself faced with a tradeoff of building a simple model nobody believes or not being able to calculate the optimal policy, Hayek is sending you a greeting card from the past: "Remember that the information contained in prices is difficult to centralise".

Tuesday, 11 February 2014

cyberloafing is the new procrastination

Lucy Kellaway is presenting some apps today to help you reduce your online procrastination, or as it is now called, cyberloafing. She quotes an analogy by David Ryan Polgar that compares surfing the web with eating junk food:

"He says we are getting mentally obese: we binge on junk information, with the result that our brains become so sluggish they are good for nothing except more bingeing."So stop reading this blog, and let's get back to work.

Saturday, 8 February 2014

Take stupidity into schools

I am writing this post while reading Daniel Kahneman's "Thinking Fast and Slow", a summary of research on behavioural choice. It's a great book! And reading it actuallty makes me angry about the education system. The findings it presents, especially on cognitive biases, are of enormous importance in everybody's lives, and yet I do not recall anybody ever telling me about them. I feel this is a major deficiency.

If you haven't read the book, and if you don't have a clear idea about expressions like availability heuristic, survivorship bias, decoy effect, and framing effect, then you are not alone. Luckily though, the ideas are easy to grasp and familiar to most people. For example, the framing effect is simply the tendency of people to see identical information less or more favourably dependent on the context in which it is delivered. People are a lot more likely to endorse a certain medication when told "it will have the desired effect 60% of the time" than when told "it will not have the desired effect 40% of the time". Stupid, right? But it is a well-documented empirical regularity in human behaviour.

Now even if you didn't know the word "framing effect", you would maybe say that you know this already. Of course people get tricked all the time. But what Kahneman repeatedly notes in his book is that, although we may know about these biases, we don't think they apply to us personally. Surely, if we were presented with the 60%-40% example above, we think we won't make this easy mistake. And yet we will. Over and over again, even when presented with evidence to the contrary. In fact, in many of the studies Kahneman documents, test subjects who were shown recordings of themselves making clearly biased judgements refused to believe that the recordings were genuine!

The important point to realise, I think, is that these cognitive biases are not just curiosities that make for good cocktail party conversation. They constantly lead to us making decisions that we will regret, and for society as a whole, cause huge inefficiencies. Their effect is pervasive. Whether we are aware of them and how we deal with them matters: Each time we buy a suit. Each time we buy an insurance policy. And each time we sell a suit or an insurance policy, manage our finances, or go to a job interview. In each case, the more biases are at play, the more likely the outcome is inefficient for society, since we end up buyings things we don't need, selling things other people don't need, not getting the job we are made for, hiring someone who isn't made for the job etc.

This is not even to mention the impact of cognitive biases on election outcomes in democracies. History abounds with examples of voters electing demagogues, and every politician knows: to win votes is to exploit voters' cognitive biases. This vulnerability of the democratic system is inherent in its construction. Ultimately, the faith in democracy stems from the belief that every citizen is rational enough to be able to decide on his or her government. Seeing the citizen in this way was a major achievement of the Enlightenment. But in soem circumstances it might be too idealistic.

Fortunately, something can be done about this deficiency. We need to anchor the teaching of "practical psychology" in the school curriculum to ensure every citizen is equipped with the knowledge of his or her stupidity. By "practical psychology", I mean those insights from psychology which concern our every day lives, including the study of cognitive biases, but also best practices on how to make decisions, memorise things or rid oneself of bad habits. More remote fields such as dream interpretation, pathologies or psychotherapy would be excluded.

Is this a sensible proposal? I think it is, but there are at least four main ways to attack it.

Attack 1: Cognitive biases don't really matter. People frequently make mistakes, but they err on both sides. Sometimes they will be led to buy a bit too much and sometimes a bit too little. On average, that just washes out.

Defense: Especially economists have a deep belief in this kind of argument. Just about any economic model is built on the ideal of the rational agent with infinite information processing capacity, and the evidence presented by Kahneman and others can only be reconciled with this ideal if deviations from it are subject to some law of large numbers. But it is far from clear that these deviations really have zero mean. Sellers are usually better at manipulating buyers than the other way around. The mere existence of consumer protection testifies to this. Also, some decisions are made once-in-a-lifetime, like buying a house. The mistake you make on that one occasion is very relevant to you as an individual, even if across individuals the mistakes average out.

Attack 2: Teaching this stuff in school won't improve people's behaviour. Kahneman himself says that cognitive biases are almost impossible to overcome.

Defense: This is probably true (although apparently there exist various attempts at teaching "debiasing"). Still, this does not mean that knowledge of such "practical psychology" won't improve our society. Even though I am not able to overcome the psychological sales tactics of my banker, I can still insist to call him back about my investment decision after a good night's sleep, even if at the moment to me his case appears fully waterproof.

Attack 3: This would be a good idea, but you can't teach this in school. It is about being streetsmart, and either you get that or you don't.

Defense: This is a very powerful argument. I forgot most of my school curriculum already. So why would pupils remember cognitive biases? But I think this is so close to our lives that it would stick. We could make the teaching very practical, very example-based. Besides, I recall so many debates that we were required to make in various subjects. Had I known about the psychology behind it, the techniques of persuasion, I would have been much more interested in them.

Attack 4: You cannot teach everything in school. Because of the limited time the pupils have, choices need to be made. This is simply not as important as other subjects.

Defense: By that logic, geography doesn't belong in the school curriculum at all.

No, this is a sensible proposal with huge upside. Adolescents in school don't only need to know the facts about the world, they also need to know how not to screw up. The introduction of financial literacy courses in Britain is a step in the right direction. When people get tricked by their bankers, the solution is neither to sob about declining moral values, nor to construct a nanny-state which regulates every aspect of consumer finance, but to empower people to make better decisions (even though the usual suspects disagree).

On a broader scale, our school curriculum is extremely slow-moving, at least in my home country Germany. In many parts it still seems to represent education ideals of the 19th century. Why do they make our children remember poems by heart? Regurgitate the list of Egyptian pharaos or Presidents of the United States? You can easily find out about this on Wikipedia. What I think is more important in a world where the individual has to take on ever more decisions is to teach people from an early age that everybody around them is stupid, that they themselves are no better, and what they can do about it.

Saturday, 18 January 2014

some great tune

Here's a piece by Charlie Haden called "Nightfall". The piano solo is really beautiful (and so simple!).

Friday, 17 January 2014

macro models taken at face value

I've been thinking a bit more about complete markets. Funnily, it was the first economic concept that I got in touch with in my math undergrad, although all I learnt about it back then was that it meant injectivity of the mapping from the probability space to the payoff space, which was good for throwing some measure theory at it.

Basically, in an economy with complete markets it is possible to costlessly write perfectly enforcible financial contracts on any current or future event and trade them on a competitive market. It's hard to explain in basic language, because it's pretty far from reality. If the world was a roulette game, then complete markets would be the existence of a competitive exchange in which a set of 37 assets are traded before each spin of the wheel, each paying off a fixed sum in the event that the roulette ball falls into the corresponding pocket.

The concept is applied quite pervasively in macroeconomics, international economics and finance, and forms the starting point for almost every analysis (at least that's what I've been taught). Imposing it has some very strong consequences. One is that, assuming standard preferences, consumption growth equalises among all agents. So consumption comoves perfectly between any two agents inside a country, and consumption per capita comoves perfectly across countries. In other words, the ratio of consumption per capita never changes across countries and within countries.

Of course, such a model prediction is just nuts. You needn't even look at data to know it won't fit. Just for fun, I made a few graphs anyway showing consumption per capita across countries. If two countries participate in complete markets, then the prediction is that the ratio of their consumption per capita is constant. So here are the relevant ratios of some countries with respect to Germany (sorry for the home bias in choosing a reference point). The data are in PPPs straight out of the Penn World Tables.

Here are some Western economies:

And some Emerging Markets:

Of course, consumption per capita relative to Germany is not constant (not within the Eurozone and not outside of it). A country like Singapore has caught up enormously while the difference to France has come down (if you believe the PWT of course).

Clearly, complete markets are not a good idea to describe long-run consumption growth across countries. I think that's mostly due to the implicit assumption that agents know, observe and can contract on exogenous shocks, whereas in reality we don't even know what those shocks are (see also my earlier post).

Unfortunately, complete markets lead to bad predictionsat business cycle frequency, too (see Heathcote & Perri ). And in closed-economy macro, they don't depict reality well either, since they essentially move a model towards a representative consumer environment which has been countlessly criticised (Noah Smith's latest post on the Euler equation is a case in point).

And yet, complete markets are the assumption you start with in macro and international macro. Why is that? The easiest answer is that it simplifies things in a model. It essentially allows you to have a representative consumer, which is more convenient for anyone who i) doesn't want to spend much time on getting a model started, ii) cares only about the supply side, or iii) wants to draw easy policy conclusions without distributional issues. In any case, you can focus on other things you want to analyse. That's a reasonable point of view: As economists, we produce models as stories to explain certain aspects of the economic sphere, and some models fit some purposes and others fit others. After all, we economists are not trying to have a unified theory that is consistent with all aspects of our data at once. Of course physics, the science we are said to envy, is aiming at exactly that, but that's different.

What I want to get at is that this scientific leap of faith is not particular to complete markets. As economists, we often build models to shed light on some aspect of the economy, complete of course with testing, calibrating, estimating against selected aspects of economic data. But the building blocks of these models, if taken at face value, provide many more predictions about the data than those we analyse, and a lot of them are completely at odds with the data! Calvo pricing, the exogenous TFP process, Modigliani-Miller, the Euler equation, default rates with credit frictions, the representative agent, the CRS production function, Nash equilibrium, even expected utility maximisation, you name it.

Now here's something odd: Sometimes, people use counterfactual model predictions to strike down a paper, and sometimes they are just okay with them. I cannot discern a pattern in this! It makes me feel I'm completely missing something in my field.

Take the attacks on New Keynesian models. Many people say these models aren't valid because they imply that individual firms change prices very infrequently, which is not true in the data. On the other hand, I have never seen anybody criticise a model because it has an Euler equation, although that also implies counterfactual model predictions on consumption growth. Is there a rule that justifies which type of counterfactual model predictions are acceptable and which aren't? Or maybe it's just okay as long as the paper is "convincing"?

One candidate for a rule could be that counterfactual predictions are okay as long as they're "microfounded". I'm not sure what microfoundations are but I think it means that a model outcome is the result of agents' choices in some constrained optimisation problem in which there is no a priori restriction on choices, only a weighing of costs and benefits. Is this the right way to go? There has been a formidable exchange of views on this position recently (e.g. here, here and here); in any event, the complete markets predictions would pass this test.

Another rule could be that models delivering counterfactual predictions are acceptable if the predictions would actually be accurate under some ideal conditions. That is a very powerful argument, and part of the bread and butter of natural sciences. One standard comparison is to the concept of gravity in elementary physics. The theory states that the gravitational force is such that any object is pulled towards the ground with constant acceleration. In particular, a feather and a cannonball thrown horizontally from the same height are predicted to reach the ground at the same time. That's of course completely at odds with what we usually observe, but it is only so because of air friction (and, as I just learned from Wikipedia, buoyancy). In a vacuum, the "model prediction" fits the data perfectly. So it makes sense to start from the constant acceleration model and then factor in other effects afterwards, which involve more complex calculations.

In the same way, we can argue that consumption behaviour under complete markets, or the representative agent Euler equation etc., would be accurate depictions of reality in an idealised economic setting. Then, if we want to make predictions for the world we live in, we start from there and incorporate all kinds of frictions. Such is indeed the agenda of a good part of macroeconomics, where entire research programmes study how to extend the standard neoclassical models by including heterogenous agents, occasionally binding borrowing constraints, private information, endogenously incomplete markets, rational inattention and much more.

But it's not so clear whether this is a good strategy in economics, even if it is successful in physics. There, we can actually create the idealised conditions and do experiments - we can generate a vacuum and test constant gravitational acceleration - or in their absence we can make repeated experiments to measure the deviation from the prediction and find regularities in that. This is difficult to do in economics, and particularly macroeconomics, where we can rarely do experiments. As a consequence, the idealised conditions and the predicted behaviour are often not the product of experimental research but of some axiomatic approach, like expected utility maximisation or Nash bargaining. To my taste, the justification that the data don't fit because of some missing "friction" becomes a bit weak.

But there is still a very pragmatic merit to thinking in these terms: They provide a common, simple framework that we can use to start thinking about things. We as economists might not understand every paper with its particular setup, but we all understand complete markets, and so we can exchange ideas starting from there. And when we want to analyse a new problem, we have a baseline from which to start exploring. In this sense, we're functioning a bit like an expedition into some unknown land: we build a basecamp where we are comfortable and safe, and then explore the territory from there. When we get stuck and the terrain becomes too difficult, we can always return to the basecamp to devise a new strategy and try again the next day. That way, when we want to think about inflation inertia, we can start with Rotemberg or Calvo pricing and develop our ideas from there, even if we don't think it's a good description of the world - at least it's a starting point. I can see nothing wrong with this approach. The only caveat with it is that we have to be ready to move our basecamp as we explore our territory further. There is no guarantee that the initial spot we picked will remain ideal forever (it might only be a local optimum, so to say). I guess that is what behavioural economists are trying to convince the rest of the profession of for some while now. They yet have to show that their "basecamp" is the more useful one, but usefulness should really be the main criterion. To use a really heavy-handed analogy: You can perfectly describe the motions of planets using a geocentric system by putting in lots and lots of frictions. But what people eventually discovered was that it is much easier to start from a heliocentric system, for which you need much fewer "frictions" to get rid of counterfactual predictions. Of course moving that basecamp wasn't particularly easy either.

In any case, criticising fundamental building blocks is easy, but coming up with alternatives is hard. The alternatives to the neoclassical DSGE "basecamp" that are out there are obscure and/or unwieldy (naturally, since the status quo has been worked on more). Certainly, I don't really have the competence to plant a new basecamp. Nor would it be wise to start working on that: First I have to finish my PhD...

Basically, in an economy with complete markets it is possible to costlessly write perfectly enforcible financial contracts on any current or future event and trade them on a competitive market. It's hard to explain in basic language, because it's pretty far from reality. If the world was a roulette game, then complete markets would be the existence of a competitive exchange in which a set of 37 assets are traded before each spin of the wheel, each paying off a fixed sum in the event that the roulette ball falls into the corresponding pocket.

The concept is applied quite pervasively in macroeconomics, international economics and finance, and forms the starting point for almost every analysis (at least that's what I've been taught). Imposing it has some very strong consequences. One is that, assuming standard preferences, consumption growth equalises among all agents. So consumption comoves perfectly between any two agents inside a country, and consumption per capita comoves perfectly across countries. In other words, the ratio of consumption per capita never changes across countries and within countries.

Of course, such a model prediction is just nuts. You needn't even look at data to know it won't fit. Just for fun, I made a few graphs anyway showing consumption per capita across countries. If two countries participate in complete markets, then the prediction is that the ratio of their consumption per capita is constant. So here are the relevant ratios of some countries with respect to Germany (sorry for the home bias in choosing a reference point). The data are in PPPs straight out of the Penn World Tables.

Here are some Western economies:

And some Emerging Markets:

Clearly, complete markets are not a good idea to describe long-run consumption growth across countries. I think that's mostly due to the implicit assumption that agents know, observe and can contract on exogenous shocks, whereas in reality we don't even know what those shocks are (see also my earlier post).

Unfortunately, complete markets lead to bad predictionsat business cycle frequency, too (see Heathcote & Perri ). And in closed-economy macro, they don't depict reality well either, since they essentially move a model towards a representative consumer environment which has been countlessly criticised (Noah Smith's latest post on the Euler equation is a case in point).

And yet, complete markets are the assumption you start with in macro and international macro. Why is that? The easiest answer is that it simplifies things in a model. It essentially allows you to have a representative consumer, which is more convenient for anyone who i) doesn't want to spend much time on getting a model started, ii) cares only about the supply side, or iii) wants to draw easy policy conclusions without distributional issues. In any case, you can focus on other things you want to analyse. That's a reasonable point of view: As economists, we produce models as stories to explain certain aspects of the economic sphere, and some models fit some purposes and others fit others. After all, we economists are not trying to have a unified theory that is consistent with all aspects of our data at once. Of course physics, the science we are said to envy, is aiming at exactly that, but that's different.

What I want to get at is that this scientific leap of faith is not particular to complete markets. As economists, we often build models to shed light on some aspect of the economy, complete of course with testing, calibrating, estimating against selected aspects of economic data. But the building blocks of these models, if taken at face value, provide many more predictions about the data than those we analyse, and a lot of them are completely at odds with the data! Calvo pricing, the exogenous TFP process, Modigliani-Miller, the Euler equation, default rates with credit frictions, the representative agent, the CRS production function, Nash equilibrium, even expected utility maximisation, you name it.

Now here's something odd: Sometimes, people use counterfactual model predictions to strike down a paper, and sometimes they are just okay with them. I cannot discern a pattern in this! It makes me feel I'm completely missing something in my field.

Take the attacks on New Keynesian models. Many people say these models aren't valid because they imply that individual firms change prices very infrequently, which is not true in the data. On the other hand, I have never seen anybody criticise a model because it has an Euler equation, although that also implies counterfactual model predictions on consumption growth. Is there a rule that justifies which type of counterfactual model predictions are acceptable and which aren't? Or maybe it's just okay as long as the paper is "convincing"?

One candidate for a rule could be that counterfactual predictions are okay as long as they're "microfounded". I'm not sure what microfoundations are but I think it means that a model outcome is the result of agents' choices in some constrained optimisation problem in which there is no a priori restriction on choices, only a weighing of costs and benefits. Is this the right way to go? There has been a formidable exchange of views on this position recently (e.g. here, here and here); in any event, the complete markets predictions would pass this test.

Another rule could be that models delivering counterfactual predictions are acceptable if the predictions would actually be accurate under some ideal conditions. That is a very powerful argument, and part of the bread and butter of natural sciences. One standard comparison is to the concept of gravity in elementary physics. The theory states that the gravitational force is such that any object is pulled towards the ground with constant acceleration. In particular, a feather and a cannonball thrown horizontally from the same height are predicted to reach the ground at the same time. That's of course completely at odds with what we usually observe, but it is only so because of air friction (and, as I just learned from Wikipedia, buoyancy). In a vacuum, the "model prediction" fits the data perfectly. So it makes sense to start from the constant acceleration model and then factor in other effects afterwards, which involve more complex calculations.

In the same way, we can argue that consumption behaviour under complete markets, or the representative agent Euler equation etc., would be accurate depictions of reality in an idealised economic setting. Then, if we want to make predictions for the world we live in, we start from there and incorporate all kinds of frictions. Such is indeed the agenda of a good part of macroeconomics, where entire research programmes study how to extend the standard neoclassical models by including heterogenous agents, occasionally binding borrowing constraints, private information, endogenously incomplete markets, rational inattention and much more.

But it's not so clear whether this is a good strategy in economics, even if it is successful in physics. There, we can actually create the idealised conditions and do experiments - we can generate a vacuum and test constant gravitational acceleration - or in their absence we can make repeated experiments to measure the deviation from the prediction and find regularities in that. This is difficult to do in economics, and particularly macroeconomics, where we can rarely do experiments. As a consequence, the idealised conditions and the predicted behaviour are often not the product of experimental research but of some axiomatic approach, like expected utility maximisation or Nash bargaining. To my taste, the justification that the data don't fit because of some missing "friction" becomes a bit weak.

But there is still a very pragmatic merit to thinking in these terms: They provide a common, simple framework that we can use to start thinking about things. We as economists might not understand every paper with its particular setup, but we all understand complete markets, and so we can exchange ideas starting from there. And when we want to analyse a new problem, we have a baseline from which to start exploring. In this sense, we're functioning a bit like an expedition into some unknown land: we build a basecamp where we are comfortable and safe, and then explore the territory from there. When we get stuck and the terrain becomes too difficult, we can always return to the basecamp to devise a new strategy and try again the next day. That way, when we want to think about inflation inertia, we can start with Rotemberg or Calvo pricing and develop our ideas from there, even if we don't think it's a good description of the world - at least it's a starting point. I can see nothing wrong with this approach. The only caveat with it is that we have to be ready to move our basecamp as we explore our territory further. There is no guarantee that the initial spot we picked will remain ideal forever (it might only be a local optimum, so to say). I guess that is what behavioural economists are trying to convince the rest of the profession of for some while now. They yet have to show that their "basecamp" is the more useful one, but usefulness should really be the main criterion. To use a really heavy-handed analogy: You can perfectly describe the motions of planets using a geocentric system by putting in lots and lots of frictions. But what people eventually discovered was that it is much easier to start from a heliocentric system, for which you need much fewer "frictions" to get rid of counterfactual predictions. Of course moving that basecamp wasn't particularly easy either.

In any case, criticising fundamental building blocks is easy, but coming up with alternatives is hard. The alternatives to the neoclassical DSGE "basecamp" that are out there are obscure and/or unwieldy (naturally, since the status quo has been worked on more). Certainly, I don't really have the competence to plant a new basecamp. Nor would it be wise to start working on that: First I have to finish my PhD...

Wednesday, 15 January 2014

"Grüner Wirtschaftsliberalismus"? Loske in der FAZ

Heute ist in der FAZ ein nicht nur innovativer und unkonventioneller, sondern auch exzellent geschriebener Artikel von Prof. Reinhard Loske (U Witten/Herdecke) erschienen.

Loske skizziert darin eine Vision, wie der Liberalismus in Deutschland, der spätestens mit dem Rausschmiss der FDP aus dem Bundestag kein politisches Zuhause mehr hat, in der Partei der Grünen wieder zu neuem Leben finden könnte. Die Verbindung von ökologischen Zielen und liberalen Grundwerten könne einen neuen Gesellschaftsentwurf produzieren, und nebenbei einen Kontrast bilden zur grossen Koalition mit "ihrem Hang zu Etatismus, Korporatismus und „großen Lösungen“". Diese Idee, so Loske, werde derzeit verstärkt bei den Grünen intern diskutiert.

Für mich ist der Artikel eine Art Offenbarung gewesen, denn mit Liberalismus habe ich die Grünen wirklich nie assoziiert. Tatsächlich sind die Grünen in meiner Vorstellung immer eine Verbotspartei aus wirtschaftsfremden Geisteswissenschaftlern, Alt-Achtundsechzigern und zuckerfreien Müttern. Das entspricht wahrscheinlich nicht der objektiven Realität, wohl aber meinen subjektiven Erfahrungen. Nur ein Beispiel: Die B31 ist eine wichtige Verkehrsachse in Süddeutschland und führt mitten durch Freiburg im Breisgau, einer Hochburg der Grünen. Pläne, die Stadt vom Verkehr zu entlasten, gibt es seit den siebziger Jahren. Aber erst 2002 wurde der östliche Teil Freiburgs mit einem Tunnel versehen, und der westliche Teil ist immer noch in Planung. Daran sind nicht nur knappe öffentliche Kassen schuld, sondern auch Widerstand der Grünen. Diese wollten die durch den Tunnelbau bedingten Eingriffe in die Natur nicht hinnehmen - unvergessen die Baumbesteiger, die den Tunnelbau in letzter Minute verhindern wollten - und argumentierten ausserdem, durch den Tunnelbau würden mehr Anreize zum Autofahren gesetzt, wo die richtige Lösung doch im Umstieg auf ökologischere Verkehrsmittel wie die Schiene bestünde. Sie setzten weiterhin im noch oberirdisch verlaufenden Teil ein Tempolimit 30 km/h von 22 Uhr bis 6 Uhr durch. Damit ist die B31 vielleicht die einzige vierspurig ausgebaute Strasse mit Tempolimit 30 in Deutschland. Weitsichtige Stadtplanung sieht anders aus.

Dieses Beispiel reiht sich ein in eine Reihe von Fällen, in denen die Grünen vor allem als Partei des Stillstands in Erscheinung getreten sind. Dazu gehört der desaströse Protest gegen Stuttgart 21 aus Gründen des Baumerhalts und Borkenkäferschutzes, gleichartige Proteste gegen das Hamburger Airbuswerk, sowie eine feindliche Grundeinstellung gegen die meisten Hochtechnologien wie Atomkraft, Gentechnik, Automobil und Mobiltelefonie. Auch Freihandel ist nicht gerade ein hehres Ideal der Grünen und ihrer Anhänger. Mittel zur Durchsetzung der politischen Ziele sind oft Blockade, Verbot oder Vorschrift. Letztere zeigt sich z.B. im Kampf der Grünen für die Frauenquote. Ich bin bei weitem kein Gegner grüner Ziele wie einem vorsichtigeren Umgang mit der Atomkraft oder mehr Chancengleichheit für Frauen. Aber das Bild, das ich bisher von den Grünen habe, hat mit Liberalismus so viel zu tun wie ein G8-Protest mit einem G8-Gipfel.

Umso vielversprechender ist es, wenn Reinhard Loske nun die Synthese aus Ökologie und Liberalismus fordert. Ist es mit der Partei zu machen? Ich weiss es nicht. Aber dieser Gegensatz erscheint mir als einer der ganz grossen unserer Zeit, und seine Synthese hätte das Potential für eine grosse politische Strömung.

Den Gegensatz stellt Loske pointiert heraus:

Kann es nicht auch sein, dass manche ökologischen Einsichten und Notwendigkeiten mit dem politischen Liberalismus gar nicht zu vereinbaren sind? Muss nicht, wer für eine Regionalisierung des Wirtschaftens eintritt, globale Freihandelsregime per se kritisch sehen? Muss nicht, wer den Überkonsum der reichen Industriestaaten als eine der Hauptursachen der Umweltkrise ausgemacht hat, der gleißenden Warenwelt und ihrer stetigen Expansion schon im Grundsatz ablehnend gegenüberstehen? Kurzum: Muss, wer die planetaren Grenzen als Realität erkannt hat, „Freiheit in Verantwortung“ nicht ganz anders buchstabieren, als der Liberale es tut, dem individuelle Selbsterfüllung das Höchste ist?

Die Synthese, die er vorschlägt, ist der Größe des Gegensatzes entsprechend nur bruchstückhaft. Gut gefallen hat mir aber der Abschnitt über die Energiewende:

Obwohl allen klar ist, dass die größten und kostengünstigsten Potentiale zur Kohlendioxid-Vermeidung in der Einsparung von Energie liegen, fließen Unmengen von Geld in den unkoordinierten Ausbau der erneuerbaren Energien, die sich überdies zunehmend als Problem der Landschaftsverschandelung erweisen. [...] Eine Politik, die ökologische und freiheitliche Ziele verbindet, wird hier ansetzen. Sie wird einerseits klare Klimaschutzziele über einen langen Zeitraum verlässlich festlegen, damit alle Akteure wissen, woran sie sind. Zum anderen wird sie die Subventionierung der fossilen Energieträger beenden und die der erneuerbaren Energieträger schneller und deutlicher zurückfahren; sie wird der ökologischen Steuerreform eine zweite Chance geben und den Emissionshandel wieder zu einem scharfen Schwert der Klimapolitik machen, kurzum: Sie wird alles dafür tun, dass die Preise die ökologische Wahrheit sagen und so Anreize zu intelligenterer Energienutzung gegeben werden.

Diesen Ansatz würde ich sofort unterschreiben. Der Liberalismus ist von der Realität zunehmend in eine Ecke gedrängt worden. Das Problem der Umweltverschmutzung, aber auch die Finanzkrise der letzten Jahre, zeigen der Vision von der "unsichtbaren Hand" immer schärfere Grenzen auf. Gleichzeitig hat der Zerfall der Sowjetunion aber auch die Unumgänglichkeit marktwirtschaftlicher und liberaler Prinzipien für das Funktionieren einer modernen Gesellschaft aufgezeigt. Keine Frage, dass der Liberalismus weiterhin Teil des Fundaments unserer Gesellschaft bleiben muss.

Ökonomen drücken die Grenzen des Liberalismus mit den Konzepten von "unvollständigen Märkten" und "Externalitäten" aus. Diese führen dazu, dass die unsichtbare Hand von Adam Smith in Gestalt des "ersten Wohlfahrtstheorems" nicht funktioniert. In meiner Interpretation eines ökologischen Liberalismus ist diese Erkenntnis der Ausgangspunkt. Die richtige Antwort darauf besteht aber nicht darin, den Bürger durch Verbote in seinem Selbsttrieb in die Schranken zu weisen, sondern durch geschickte gesellschaftliche Mechanismen die richtigen Anreize zu setzen. Im Beispiel der Energiewende bedeutet das, Energiepreise die ökologischen Kosten widerspiegeln zu lassen, und im Übrigen es den Bürgern und ihren Märkten die Frage zu überlassen, wie Energieeffizienz am besten erreicht werden kann. Es würde bedeuten, den Co2-Emissionshandel ernst zu nehmen (was zur Zeit nicht der Fall ist, siehe hier), Wettbewerb zwischen Energieanbietern zu erhöhen und im Gegenzug Verbraucher steigende Energiepreise nicht zu verheimlichen. Dieser ökologische Liberalismus erkennt die zentrale Botschaft Friedrich Hayeks voll an: dass staatliche, bürokratische Planung nie die Informationen verarbeiten kann, die Märkte dezentral koordinieren. Dort, wo Märkte von freien Bürgern versagen, müssen sie behutsam umstrukturiert, aber nicht ersetzt werden. Die Freiheit des Bürgers darf nicht beschnitten werden, sondern es muss ihm schmackhaft sein, seine freie Entscheidung im Sinne der Gesellschaft zu treffen. Wenn das auch ohne staatlichen Eingriff der Fall ist, umso besser.

Wednesday, 8 January 2014

business cycle insurance

I am trying to write a paper on the economic impact of an EU-wide unemployment insurance mechanism (joint with Stephane Moyen and Nikolai Staehler from the Bundesbank). Such a mechanism has been suggested, among others, by EC President van Rompuy and IMF staff. The basic idea is that unemployment insurance might be a simple and implementable way of sharing cross-country risk. Country-specific booms and recessions could be mitigated through transfers among EU member states which take place through differences in contributions paid to and benefits drawn from a common unemployment insurance scheme.

But after a few discussions, I have had to learn that the appeal of cross-country insurance is difficult to sell. This could be a result of my meager sales skills, but I suspect there is something deeper in the resistance to this type of business cycle insurance.

That insurance in general is desirable is the same as saying that people are risk averse, which is not all too disputable. If you know that your house can be destroyed in a fire, then you probably like taking out a fire insurance contract. Most of the time, you pay an insurance company money without getting anything in return, but in the event of a fire you get a lot of money to compensate for the damage to your house. This prevents you from having to make big cuts in your consumption and to run down your lifetime savings when you need to rebuild your house. On the other side, the insurance company is able to provide you such a contract because it pools risk: It receives small payments from a large number of people whose house is not burning and makes large payments to a few people whose house is burning.

The last paragraph is so commonplace it's almost a waste of space. But now replace "house" with "country" and "fire" with "recession", and it becomes a highly controversial issue. Why? What's wrong with building a cross-country insurance mechanism in the EU, for example through a common unemployment insurance system, which every year pays out transfers to countries in a recession and collects premia from countries with healthy economies?

There are numerous attacks on the proposal: the difficulty of measuring recessions as opposed to structural changes, the political viability, the size of welfare gains, and correlation of business cycles across countries, to name just some of the most frequent ones. But the one argument that dominates any debate about a European "transfer union" is moral hazard: Germans don't want to pay for Spaniards and Greeks because they suspect that doing so prevents reforms in those countries and perpetuates the alleged laziness of their workers and politicans.

Moral hazard in general is a powerful argument against insurance. It can also be applied to fire insurance, where it amounts to saying that taking out insurance will make homeowners set fires on purpose or make them less willing to take precautionary measures to prevent fires . The first problem is not very large: few people want to commit insurance fraud if it means setting their own house on fire. The second problem is more relevant, and insurers write clauses that preclude payment when obvious fire prevention measures haven't been taken. But nobody questions the usefulness of fire insurance in general. This is because fire is regarded as an exogenous event: we believe it generally happens unexpectedly to people and without them being able to affect its occurence.

Modern macroeconomic modeling practice sees a recession much in the same way as a fire: it is caused by an exogenous shock, outside of the control of agents in the model. Unexpectedly, productivity drops, credit tightens, people become thrifty or lazy. Yet many people, including economists I have spoken to about our paper, are worried that introducing insurance against business cycle risk would somehow lead to more, longer or deeper recessions, as if this was something in people's control.

So do economists really believe that business cycles are caused by exogenous shocks? I don't think so. It's simply too much to stand up and say that a recession is just "bad luck". It's also not what economic advisors are paid for. Instead, economists spend most of our times explaining the latest business cycle episode as an endogenous build-up: now, the financial crisis was caused by reckless overborrowing and taking on systemic financial risk, whereas before the crisis, the preceding boom was said to be the endogenous product of successful financial deregulation, "anchored expectations" and lower trade costs, among other things. To get more in the European context, the fact that Germany is not in a recession but Spain is is most often attributed to differences in labour market, industrial and general fiscal policies. It is not attributed to Spain getting some random bad shock and Germany getting a random good shock. And if business cycles are the products of the vice and virtue of governments and citizens, then obviously you shouldn't insure them against bad outcomes!

The problem is that any narrative about endogenous causes of business cycles runs into problems with modern macroeconomic and macroeconometric methods. There, we model business cycles not as "cycles", but as outcomes of a small set of random shocks. Econometrically, it is hard to predict business cycles, hence the estimations attribute them to random shocks. Theoretically, endogenous business cycles are really hard to produce as well: them being endogenous implies that their existence is due to agents' choices. But standard theories abound with rational expectations, optimising agents, perfect information and efficient markets, which means that agents disliking large fluctuations will not make such choices.

In principle, the same urge for endogenisation applies to houses on fire. If your house burns down because of a leaking gas pipe, even if this gas pipe was properly and regularly checked, you will probably blame it on the gas engineer, or on your decision to have a house with gas heating. But at some point, at least from a social perspective, we accept that fires just sometimes happen, that it is bad luck, and that people should be able to insure against it. The only place where we think otherwise is insurance fraud. But as mentioned, this is a rare thing. Likewise, it would probably be strange to argue that the main moral hazard issue in cross-country insurance were that it would induce the governments of Southern Europe to trigger recessions on purpose in order to claim transfers from the North. After all, how many people would want to set their own house on fire even if they get some insurance money for it?

But of course, it's not only about what caused the fire, but what you did to prevent it, or mitigate its spreading through your house. In the same spirit, one can argue that recessions are indeed caused by exogenous shocks, but that the reaction of some country's economy to those shocks is endogenous. For example, Spain could make itself more resistant to business cycles by reforming its labour market towards more flexibility; a European insurance mechanism might destroy the incentives to do so. That is a valid point.

There is a great Econometrica paper by Persson and Tabellini that makes this point theoretically, using a stylised and static political economy model. Unfortunately though, it is hard to make it within the context of business cycle macroeconomics, which hardly ever considers endogenous government policies. Bridging this gap between political economy and business cycle theory seems a daunting task. And how would one go about calibrating moral hazard of national governments to data? The deeper problem here, I think, is that economics offers no good framework how governments actually make choices; and the only framework of how they should make choices, namely as benevolent, rational, optimising social planners, is inadequate to the problem.

But after a few discussions, I have had to learn that the appeal of cross-country insurance is difficult to sell. This could be a result of my meager sales skills, but I suspect there is something deeper in the resistance to this type of business cycle insurance.

That insurance in general is desirable is the same as saying that people are risk averse, which is not all too disputable. If you know that your house can be destroyed in a fire, then you probably like taking out a fire insurance contract. Most of the time, you pay an insurance company money without getting anything in return, but in the event of a fire you get a lot of money to compensate for the damage to your house. This prevents you from having to make big cuts in your consumption and to run down your lifetime savings when you need to rebuild your house. On the other side, the insurance company is able to provide you such a contract because it pools risk: It receives small payments from a large number of people whose house is not burning and makes large payments to a few people whose house is burning.

The last paragraph is so commonplace it's almost a waste of space. But now replace "house" with "country" and "fire" with "recession", and it becomes a highly controversial issue. Why? What's wrong with building a cross-country insurance mechanism in the EU, for example through a common unemployment insurance system, which every year pays out transfers to countries in a recession and collects premia from countries with healthy economies?

There are numerous attacks on the proposal: the difficulty of measuring recessions as opposed to structural changes, the political viability, the size of welfare gains, and correlation of business cycles across countries, to name just some of the most frequent ones. But the one argument that dominates any debate about a European "transfer union" is moral hazard: Germans don't want to pay for Spaniards and Greeks because they suspect that doing so prevents reforms in those countries and perpetuates the alleged laziness of their workers and politicans.

Moral hazard in general is a powerful argument against insurance. It can also be applied to fire insurance, where it amounts to saying that taking out insurance will make homeowners set fires on purpose or make them less willing to take precautionary measures to prevent fires . The first problem is not very large: few people want to commit insurance fraud if it means setting their own house on fire. The second problem is more relevant, and insurers write clauses that preclude payment when obvious fire prevention measures haven't been taken. But nobody questions the usefulness of fire insurance in general. This is because fire is regarded as an exogenous event: we believe it generally happens unexpectedly to people and without them being able to affect its occurence.